|

||||||

|

||||||

|

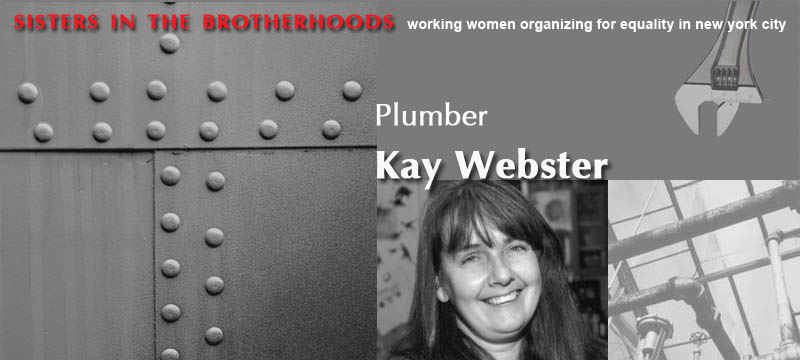

Kay Webster grew up in Buffalo, New York, the daughter of a carpenter and a homemaker who later worked for the postal service. After moving to New York City she worked as a waitress, but the low pay motivated her to pursue a career in the trades. She attended All-Craft for a time, and after working briefly as a carpenter, she switched trades. “There were a lot of women carpenters, and so I decided to take up plumbing,” she later recalled.

She was the second woman to try for a plumbers' union card. There were two routes into the union: the traditional apprenticeship program and a state-sponsored trainee program designed to counter the exclusion of minorities and women from the construction trades. Webster entered the trainee program and attended weekly classes whose hostile environment literally made her ill. She persisted, however, only to learn that the program was a dead end: trainees were not hired. While continuing to work at nonunion jobs, Webster applied to the apprenticeship program. She took the required test and underwent an interview, only to be told later that she tested badly. A skeptical Webster contacted the state and learned that her test scores were high; her interview score was the issue. She filed a discrimination suit with New York City's Human Rights Commission that resulted in revamped interview process. Webster also was offered a second-year apprenticeship, but she decided against it. "By that time, I was already on the nonunion job," she later recalled. "We were doing this project of 143 units. It was a big job, and I was the manager. Why am I going to go to the second-year apprenticeship and worker under these hideous conditions when I actually have a group of guys who I’m working with that are actually pretty good, and I’m earning enough money?" During the remainder of her 14-year career as a plumber, Webster worked solely at nonunion jobs. She remained employed during boom-and-bust cycles by doing residential projects. She also taught classes at All-Craft and at Nontraditional Employment for Women (N.E.W.) and also participated in United Tradeswomen. Currently she devotes her time to community organizing in her neighborhood and to supporting its public school. She uses her construction skills at home and on behalf of family and friends. In her oral history Webster candidly discusses her decision to follow the nonunion path, the male culture of construction trades, and the need to combat what she calls women’s “internalized message of incapacity.” |

|||||

| ||||||

Copyright 2012 Jane LaTour/Talking History Photo of Elaine Webster by Gary Schoichet |

||||||